|

Archive for the 'Turkey' Category

Simon Maghakyan on 21 Jul 2011

The United States House Foreign Affairs Committee has passed (43 yes; 1 no) an amendment calling on Turkey to return Christian properties to their rightful owners. That would be 2,200 Armenian sites (a number concluded from statistical research instructed by Turkey’s Interior Ministry to Archbishop Maghakia Ormanian from the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople during 1912-1913), as well as hundreds of Greek and Assyrians properties.

Kudos to the Armenian National Committee of America for initiating the “return of churches” campaign. While the U.S. government is very careful not to use the term “genocide,” genocide recognition can be achieved indirectly, such as addressing the cultural loss caused by the genocide. Turkey understands the last point very well; that probably explains the official Turkish anxiety over the issue.

Nonetheless, Turkey must preserve its diverse heritage – with or without acknowledging the Armenian genocide. In 1969 Turkey signed the International Treaty for the Preservation of Cultural Monuments. Moreover, Turkey has also signed the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples which underscores indigenous peoples’ “right to maintain, protect, and have access in privacy to their religious and cultural sites.”

Simon Maghakyan on 27 Nov 2010

A Facebook group in Turkish called Once upon a time Armenians in Anatolia has photographs and postcards of new and old Armenian culture in eastern Turkey.

Simon Maghakyan on 01 Sep 2010

Turkish hackers are infamous (try a simple Google news search), Russia is regarded as cyber-criminal haven, and Azerbaijan and Armenia are known for mutual cyber-attacks (what one might call ‘nagorno cyber attacks’). Web surfers in all these four countries lose at the end. According to SPAMfighter, “Internet security company AVG Technologies has revealed that web surfers in Russia, Turkey, Azerbaijan and Armenia are most likely to face risks while online.”

One argument is that internet vulnerability ultimately means stronger security – the more you are attacked, the better protection you seek.

But is this a reasonable price for the people of Armenia and Azerbaijan, technically at war over Nagorno-Karabakh and clearly responsibly, in part, for the risks in both countries, to pay?

With quality of life so low in both countries, Internet shouldn’t become a burden for users. “Information wars” are fine since they have potential for dialogue, but cyber wars, how should I say it, suck. Especially if, like me, you are not the best when it comes to protecting your computer from viruses.

Time for cyber dialogue.

Simon Maghakyan on 04 Feb 2010

Over two millennia ago, this Greek leader’s kingdom stretched from Europe to Asia. He was not Alexander the Great and his empire was much smaller. Yet he revived Greek democracy, freed slaves, inspired Mozart’s first opera but also mastered a massacre of Roman settlements in what is today western Turkey.

Controversial alike every other classical celebrity, Mirthradates the Great’s once vibrant story has nowadays deliberately disappeared largely due to, according to History Today, a genocide that took place two thousand years after the Greek king’s and his even more successful Armenian son-in-law Tigranes the Great’s times.

In the words of Adrienne Mayor:

“[…]

Why was the once renowned Mithradates the Great so forgotten? Should we blame Shakespeare for neglecting to immortalise his struggle against Rome? Or fault Marxists for favouring Spartacus, the gladiator-rebel of Thrace instead of the King of Pontus?

It is not difficult to guess why memories of both Mithradates and Tigranes have been suppressed in Turkey, which still officially denies the 1915 Ottoman genocide of Armenians in Tigranes’ old kingdom and the deportation of Greeks from Pontus, Mithradates’ philhellenic realm.

[…]”

The genocide of indigenous Anatolians (Armenians, Pontus Greeks, and Syriacs) during WWI is a timeless event. Its official Turkish denial in the 21st century is not a mere distortion of a hundred-year event, but unproductive cover-up of thousands of years of history that took place earlier.

The complete History Today article is available, upon registration, at http://www.historytoday.com/MainArticle.aspx?m=33743&amid=30295020.

Simon Maghakyan on 21 Jan 2010

After repeated silence from municipal officials regarding a name change, a civil society group in Istanbul, Turkey has itself replaced the sign of a local street from that of a mythical toponym – used by a terrorist group – to the name of an Armenian journalist murdered three years ago this month by a ultra-nationalist youth.

The teenager who shot Hrant Dink – the editor of Agos newspaper and a promoter of reconciliation between Turks and Armenians – was allegedly recruited by Ergenekon, an elite military group which has failed its goal of toppling Turkey’s Islamic but moderate administration. Ergenekon, which is named after a mythical place and is revered by Turkish ultra-nationalists, supposedly had planned to kill other Armenians as well (prominent representatives of the handful of indigenous Christians who once numbered 20% of what is today’s Turkey).

Originally reported in Turkish by Bianet, the news is quite interesting: in a nationalist country like Turkey (even in relatively liberal Istanbul), such action can be dangerous (no official or nationalist reactions have been reported so far). But it is also inspiring, and giving hope that maybe, just maybe, progressive Turks – and hopefully Turkey as a society – will one day rename streets honoring the perpetrators of the Armenian genocide as well.

In Istanbul alone, there are four avenues celebrating the main architect of the genocide – Talaat.

Simon Maghakyan on 11 Jan 2010

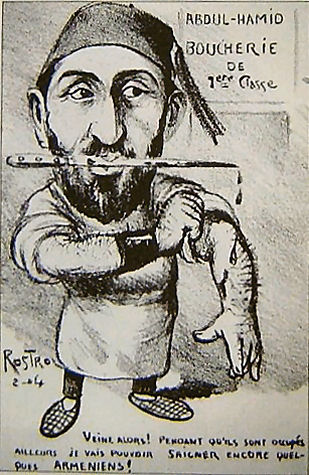

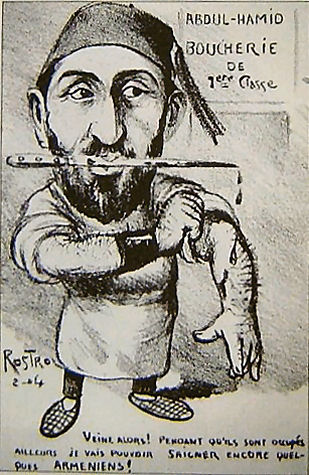

The late 19th century Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II banned the use of the scientific formula for water. He thought that H2O might be interpreted as he (Hamid the second) being equal to nothing (zero). The reverse, unfortunately, was the case: even during his rule Hamid became a world-famous figure nicknamed the “bloody sultan” – for massacring almost quarter a million Christian Armenians in the late 1890s in lieu of introducing sought reform. A decade after the Hamidian massacres, the next Ottoman regime that replaced the sultan brought about the end of what is now eastern Turkey’s indigenous Armenian population.

Over a century after the Hamidian massacres and half a decade short of the centennial of the genocide that followed, a grandson of the “bloody sultan” says he is “on the side side of the truth.” One reason why Beyzade Bülent Osman admits, even as indirectly so, his forefather’s massacres and the genocide that followed is because his family “owed their lives” to an Armenian family in France that helped Mr. Osman’s family when they escaped from the Ottoman Empire.

The Turkey-based Hurriyet has the story:

[…]

The world knows Sultan Abdülhamit II as a key name related to the Armenian issue and the events of 1915, recognized as genocide by many countries, a claim Turkey rejects. “I am on the side of truth,” Osman said on the issue. “The French and the Germans had also slaughtered each other, came into conflict but still managed to establish dialogue. We have to leave history behind us and look ahead.”

Osman also said his family “owed their lives” to French-Armenians after their exile from Turkey. “We were penniless,” he told the Daily News. “Our Armenian friends helped us. There was an Armenian lady who welcomed us to her chateau and we lived there for a long time. I cannot deny the good deeds Armenians have done for my family.”

[…]

Simon Maghakyan on 26 Oct 2009

A higher court in Turkey has returned 44 of 100 acres to an Armenian family after decades of legal battle, an unprecedented act in a country where the indigenous Armenian population was wiped out during WWI, their ancient civilization destroyed, and their private property confiscated.

But while most of the land the Christian Armenians once owned is in rural (and poor) eastern Turkey, the 44 acres the France-based Agopyan family will recover is in Istanbul’s affluent Tarabya neighborhood, located on the European shores of the Bosphorus. Estimated at billions in value, the land houses luxurious villas, historic places, night clubs and restaurants.

Sources (in Turkish):

http://haber.gazetevatan.com/haberdetay.asp?Newsid=265882&Categoryid=1

http://www.emlakkulisi.com/15237_agopian_ailesi_nin_1955_te_actigi_arazi_davasi_suruyor

Via Tamara Azarian

Simon Maghakyan on 26 Oct 2009

A contribution by a security analyst who has requested anonymity

Concerned about the “historical commission” in the Armenian-Turkish protocols that may investigate the veracity of the Armenian Genocide? You should be if you are an idealist who believes that patently obvious facts should not have to be proven again and again. For many, this endeavor is as impossible – if not as pointless – as it is to enlighten someone who intransigently insists that the sun orbits around the earth, despite that fact that science proved the opposite centuries ago. That being said, I never want to give up on someone who genuinely seeks the truth.

The Armenian “case,” also known as the truth, is quite simply unassailable no matter what tactic genocide deniers may use. This article will set out to eviscerate just one possible Turkish tactic by hypothesizing that everything the Turkish government says about “Armenian rebels” is true; that these militias didn’t simply exist as means of last ditch self-defense, but were instead instruments of insurrection and secession. (Which, nevertheless, would be fully justified after hundreds of years of oppression from a government that Armenians never contested to be part of)

The most damning evidence that shows that Turkey carried out genocide against the Armenians is a comparative analysis with the Arab Revolt. Just as a reminder, during WWI many Arabs openly sided with the British. They were resentful of heavy-handed Turkish rule, and wanted to be independent. As with most nationalist movements, this revolt initially started on a smaller scale, and ultimately mushroomed into full-scale warfare between Ottoman Turkish forces and Arabs.

So where is the “damning” evidence I am talking about? The fact of the matter is that the Ottoman Empire had the military capability to conduct the same measures against the Arabs, i.e. genocide, as they did against the Armenians. The Ottoman Government could have simply cited the same reason they used to justify the Armenian Genocide, “they were siding with the enemy (which was true in the case of the Arabs), and that the homeland must be preserved at all costs.”

As indicated by the outcome, the Arab revolt was every bit as dangerous to the Ottoman Empire as was the so-called “Armenian Revolt.” Yet, in the end the Ottoman Empire did not target Arab civilians as it did Armenian civilians. While Arab lands were still under Ottoman control, Arab residents of Damascus, Aleppo, etc were not exiled into the wasteland without food, water or shelter. Instead the Empire, for the most part, restricted its violence to actual Arab militias. Certainly, skeptical readers might say, the Arab Revolt originated in the uncontrollable and wild Arab Peninsula, not domesticated Damascus. But, this same skepticism can and should be applied to the Armenian case as well. Even the most fanatical Turkish apologist will not claim that the alleged “Armenian Revolt” existed in Bursa, Konya, etc., yet the Armenians of these Anatolian cities were nevertheless marched into the desert and slaughtered en masse. So what possible conclusion can be drawn from the comparison? The Ottoman government’s policy regarding the Armenians was not just some necessary wartime contingency.

Except wait…

Some denialist historians might say that the Ottoman Empire was ultimately willing to lose the Arabian lands. Arabia was not vital to the empire’s existence, and its loss did not represent and existential threat. Turks did not live there in significant numbers, and they were more overseers than anything else. Conversely, these historians will claim the same is not true in the Armenian case, and that Anatolia is the heartland of the ethnic Turks. Had Armenians carved out an independent country there, or so the denialist argument goes, the existence of the Turkish people would be threatened. But this argument is not valid either. Eastern Anatolia at the time was an ethnic mosaic, and rarely did Turks constitute an outright majority. In fact, in many places such as Bitlis, Armenians were the largest ethnic group followed by the Kurds. Here and in other places in the region, Turks were actually only a small minority. Therefore, the same demographic argument that says Arabia wasn’t important to Turkey also applies to Eastern Anatolia.

To this, a denialist historian might answer, demographic reality is not as important as the perception of Turks. But again, Eastern Anatolia does not feature prominently in the hearts or lore of Turks (even till this day), with one minor exception being Alp Arslan and his battle at Manzikert in the 11th century. Instead, Eastern Anatolia has always been more like a colony, such as the Balkans, than an integral part Turkish identity. The real homeland, the real gem, to Turks at the time of WWI is further west where the Ottoman Empire actually originated, places like Eskisehir.Therefore, fear of losing Eastern-Anatolia as opposed to Arabian lands is not a justification for Ottoman policies vis-à-vis the Armenians, especially when considering that the Levant is just as close to the heart of Turkish identity, western-Anatolia, as is Eastern-Anatolia.

In conclusion, the Ottoman Empire’s brutal treatment of the Armenians, even if they were in full revolt (which they weren’t), was reserved for Armenians alone, despite other rebellions in the Empire. It is now incumbent on denialist historians to explain the huge differences in policy with respect to an identical security threat. All this being said, severe annoyance with this “commission” is justified, because denialists are most likely not really looking to debate the veracity of the Armenian Genocide, but instead are mainly interested in the mere illusion of controversy.

P.S. There is no rule that says that genocide cannot occur simultaneously with war and rebellion, as Armenian Genocide deniers would mistakenly have you believe. If anything, a genocide that occurs without the backdrop of rebellion, even rebellion committed by the victim group, represents an anomaly. I am going to give just three examples of genocides coinciding with rebellion, though many more cases exist. The Rwandan Genocide of the Tutsi people coincided with the Tutsi RPF rebellion in the same country; the Herero Genocide coincided with a rebellion in German South-West Africa by the Herero; lastly the Genocide in Darfur which coincided with the JEM rebellion in Sudan. If you were to apply the same (rebellion = no genocide) argument that denialists use against the Armenian Genocide, you would have to deny every other genocide in history.

Simon Maghakyan on 04 Oct 2009

“Who controls the past controls the future;” party slogan states in George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984, “Who controls the present controls the past.”

While hopes are high that – despite a hostile history – Armenia and Turkey will establish diplomatic relations and that the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan may finally be solved, the problem of how to deal with the official Turkish/Azerbaijani factory of history is not being addressed.

Djulfa, Nakhichevan: the worst documented case of history fabrication; Azerbaijani soldiers destroying the largest Armenian medieval cemetery in the world (December 2005) – the site is now a military rifle range

It’s not merely Turkey’s and Azerbaijan’s denial of the Armenian Genocide that makes the reconciliation quite difficult, to say the least, but also the official Turkish thesis, with its roots in the Young Turkish movement (that carried out the Armenian Genocide) and formalized by Ataturk, that Turks/Azeris are indigenous to their current homelands and that Armenians, in the best case, are unwelcome immigrants.

While the Turkish fabrication of history can be dismissed as an issue of “internal consumption” – meaning a convenient myth to boost Turkish/Azeri pride in their respective countries (with the dangerous slogan “Happy is the man who can say I am Turk”) – the implications of flip-flopping history are right there in the middle of the current developments in the region. Here is a most recent case.

Turkey’s ceremonial president Abdullah Gul is currently visiting Nakhichevan (or Nakhchivan as Azerbaijan prefers), the region of Azerbaijan which it got from the communist regime in Moscow as another gift at the expense of giving out Armenian lands. Moreover, a treaty that Soviet Armenia was forced to sign from Moscow made Turkey the “guarantor” of Nakhichevan in the 1920s.

Gul is visiting Nakhichevan with other heads of “Turkic-speaking countries” (most of them in Central Asia) to talk about common issues. Sounds like a normal political event, and nothing to protest about, especially since Armenia has no official claims toward Nakhichevan. But read the rest.

As there are no Armenians left in Nakhichevan (thanks to a Soviet Azerbaijani policy of nonviolent ethnic cleansing which attracted little attention at the time) and not a trace of the rich Armenian heritage (the most precious of which, the Djulfa cemetery, was reduced to dust by Azeri soldiers in December 2005 – see the videotape), Armenia has no claims to Nakhichevan and perhaps rightly so. Yet, apparently, the history factory in Nakhichevan is still cooking.

While Armenia restraints itself from claiming its indigenous lands, and particularly Nakhichevan, taken away from it without its consent, Turkey and Azerbaijan must discontinue their unhealthy fabrications of history. Instead…

According to Trend news agency based in Azerbaijan, Turkey’s visiting president has “noted that Nakhchivan, whose name means ‘world view’, is the native and valuable for both Azerbaijan and Turkey.”

Putting the “native” side aside for a moment, the distortion of not just basic history but of linguistics is sickening. Save for the disputed proposal that Nakhichevan comes from the Persian phrase Naqsh-e-Jahan (image of the world), every other explanation of the name of the region has to do with Armenians (see Wikipedia for the several versions), let alone that the word itself has two Armenian parts to it: Nakh (before or first) and ichevan (landing, sanctuary) – referring to Noah’s coming out of the Ark from (another holy Armenian symbol) Mount Ararat – next to Nakhichevan now on Turkish territory.

Ironically, and as almost always in history fabrication, the Azeri/Turkish distortion of “Nakhichevan” is inconsistent. According to an official Azerbaijani news website, there are discussions in Nakhichevan that admit that the word has to do something with Noah (of course after saying that it had to do with a mythical Turkish tribe that lived there thousands of years ago): “The Turkic tribes of nakhch were once considered as having given the name to it. Other sources connect Nakhichevan with the prophet Noah himself, as his name sounds as nukh in Turkic.” Moreover, as an official Nakhichevani publication reads, “There is no other territory on the earth so rich with place-names connected with Noah as Nakhichevan. According to popular belief, Noah is buried in southern part of Nakhichevan, and his sister is buried in the northwest of the city.” Hold on. Did you notice that the language uses (at least its official English translation) the Armenian taboo name of the region: Nakhichevan (as opposed to Turkified Nakchivan)? Maybe there is hope, but not really. Azerbaijan still denies that it didn’t destroy the Djulfa cemetery because, well, it didn’t exist in the first place.

A skeptic would ask what the fuss is about. The answer is that Nakhichevan’s distortion is not the first. The sacred Armenian places of Ani, Van, and Akhtamar in Turkey all have official Turkish explanations to their meanings, while those places existed for hundreds – if not thousands – of more years before Turks colonized the homeland of the Armenians.

More importantly, the changing of toponyms is not done to meet the social demands of Turks/Azeris and in order to make it easier for the locals to pronounce geographic names. Distortion is done to rewrite history in order to control the future. But it’s not the right thing to do. And both Turkey and Azerbaijan embarrass themselves when it comes to legal discussions.

Immediately prior to voting for the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in September 2007, for example, the Turkish delegation at the United Nations made it clear that its “yes” vote was cast with the understanding that there were no indigenous peoples on Turkey’s territory. If there were indigenous peoples on the territory, the Turkish representative stated, then the declaration didn’t challenge states’ territorial integrity. Azerbaijan, on the other hand, abstained from voting.

The reservation on the UN document came from both countries who claim that there are the indigenous heirs of the lands they occupy and that their main enemy, Armenians (and also Kurds) are not only indigenous but are recent immigrants.

One version of Azerbaijan’s ridiculous inidigenousness claim is written on the website of one Azerbaijani Embassy: “The ancient states of Azerbaijan, which maintained political, economic and cultural ties with Sumer and Akkad and formed part of the wider civilization of Mesopotamia, were governed by dynasties of Turkic descent. The Turkophone peoples that have inhabited the area of Azerbaijan since ancient times were fire-worshippers and adherents of one of the world’s oldest religions – Zoroastrianism.”

Armenians (and to a large extent the Kurds, Assyrians and Pontiac Greeks) have their share of fault in the debate. Constantly repeating their indigenousness in what is now Turkey and Azerbaijan, Armenians have helped create the defensive Turkish/Azeri attitude that they, and not Armenians or others, are the indigenous peoples of the land. But when it comes to fabricating history of their own, there is little blame for Armenia.

As Armenia struggles to defend the victory it won over the Karabakh conflict, most Armenians use the Turko-Persian name for Nagorno-Karabakh (Karabakh meaning black garden, Kara – black in Turkish and bagh – garden in Farsi). While some Armenian nationalists prefer using the indigenous name of the region, Artsakh, many others indirectly admit that diverse history of Nagorno-Karabakh by keeping its Turkified name.

Like Armenia, Turkey and Azerbaijan must also defend what they see as their rights but not at the expense of unhealthy history fabrications. Moreover, Azeris and Armenians are genetically closer to each other than Azeris and their “brethren” (Uzbeks, Turkmen, etc.) in Central Asia. This means that, physically but not culturally speaking, both are interconnectedly indigenous.

While Turkey ad Azerbaijan must come to terms with history, Armenia must accept that Turks and Azeris are there to stay. All the nations in the region have equal rights to existence, but not so at the unhealthy price of fabricating history.

Simon Maghakyan on 22 Sep 2009

Armenian diaspora’s idealist opposition to Turkey-Armenian negotiations is understandable, but an outright rejection of the dialogue process is a missed opportunity to introduce ideas and strategies that would empower Armenia.

One of world’s ancient nations and one of its youngest states, Armenia celebrated its 18th anniversary as an independent republic on September 21, 2009.

No country in history has persisted so much invasion, persecution, and genocide.

No country has continuously existed for so long as Armenia has.

And even though today’s Armenia is small, weak and has a declining population of already less than three million, today’s Armenia is one of the best times Armenia has had in thousands of years. Today is Armenia’s gift, and that gift must be used wisely.

Already a young adult, Armenia lives in a world with little room for mistakes. It must democratize, stabilize and normalize its relations with its historic foes to survive in times when today’s errors will be hard to erase tomorrow. As bad as Armenia may seem today, it has the opportunity to invest in a great future.

As the new Armenia is celebrating its entrance to adulthood, its ongoing negotiations with Turkey are in the center of international attention. There have been many articles and discussions on a subject which divides a lot of people, who I will “divide” into two camps – pragmatists and idealists.

Armenia’s current administration, and perhaps most of the citizens in the Republic, wants to normalize relations with Turkey for economic reasons. These are the pragmatists, for who Armenia is the only permanent address they have known, and who want to have a normal social life. I understand this group well. This is the group that is Armenian every second of their life. This is the group that wants to change, improve Armenia and is willing to take the risks. This is the group that ultimately takes all the risks.

I also understand the second group – the idealists. These are the diasporans for whom the Armenian genocide is the centerpiece of Armenian identity. The diaspora would never exist in the first place if there was no genocide. Diaspora’s opposition to the Turkish-Armenian ‘normalization,’ thus, is natural. These are the people that won’t forget how Turkish governments repeatedly lied to Armenians, and how the most trusted of those, the CUP, ended up carrying out the Armenian genocide. These are also the Armenians for who genocide awareness is often the road to staying Armenian. Diasporans have to fight day and night to keep the Armenian identity – unlike the Armenians in Armenia, who – no matter what they do – are Armenians every second.

I understand both groups. I love both sides. I am a son of the genocide itself and a son of the young and small Armenia living in the Diaspora. But when it comes to making a choice for Armenia’s future, I have to be a realist.

The reality is that Armenia’s population, at its best, will stay 3 million for the next decades. Turkey’s 71 million population and Azerbaijan’s 8 million will keep growing, coupled with the rise of ethnic Turkic Azeris in northern Iran. Unless Armenia finds a language with these inconvenient neighbors, it could face the danger of a final genocide.

Finding a common language, to be clear, has nothing to do with forgetting the Armenian genocide. The pragmatists, taking a market-ly speaking neoliberal approach, think that free trade will bring dialogue, and dialogue will bring genocide recognition. The idealists, on the other hand, say that genocide recognition should come first. As noble as the latter sounds, the former seems to make most sense. “Once the border opens,” Turkish historian Taner Akcam told me a few years ago, “Armenians and Turks will find out that they have more things in common than they thought: they have the same daily problems, and none have horns.” He surely belongs in the pragmatist camp, not only in the Armenian but also in the Turkish sense.

Is it bad to be an idealist? Not at all. But the idealist opposition to the “Armenian-Turkish protocols” needs to be a constructive one. Instead of outright rejecting any normalization efforts between Armenia and Turkey, the diaspora idealists must infuse specific and stated strategies that the pragmatists have been unable to include in the negotiations:

Demand Turkish neutralization in the Nagorno-Karabakh process

Demand the US government to force Turkey to declare itself a neutral side in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

Demand Turkey that by 2015 all monuments honoring the perpetrators of the Armenian genocide have separate plaques added describing the crimes they committed during WWI

While the latter is the only point that deals with the genocide, the issue of Nagorno-Karabakh is the most realpolitik task and requires immediate attention. The idealists, overoccupied with genocide recognition, have long neglected the question of Nagorno-Karabakh – the indigenous Armenian region claimed by Azerbaijan.

Turkey remains the biggest obstacle in reaching peace in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict that will guarantee the security of the region’s indigenous population. If Turkey wants to normalize its relations with Armenia, it must stop being pro-Azerbaijani when it comes to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. It must declare itself neutral in the conflict and say that it will honor any decision reached between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

This is the chance for the idealists to make a difference in the normalization process. It’s time to tell Turkey that for Armenians to choose the pragmatist approach – open border first, dialogue second and reconciliation third – Turkey must become objective in the Nagorno-Karabakh process.

Next Page »

|

|