While I have been silent on the recent developments of the Nagorno-Karabakh peace process, it doesn’t mean I have not been following the news. My silence reflects a complicated mixture of cautious optimism, confusion, excitement, fear, cynicism, and a busy schedule (which includes observing the US presidential elections). We live in historic and unpredictable times. These unknown globalized waves can translate into almost anything in Nagorno-Karabakh – from long-term solutions to further conflict.

Internationally, Obama’s election, Georgia’s unsuccessful bid for South Ossetia, Turkey’s continuous struggle to join the European Union, and international – particularly US and Russian – interest in the South Caucasus have contributed to the recent developments in the Armenian-Azerbaijani peace process, which was vocalized in a set of principles that Azerbaijan and Armenia signed in Moscow in early November 2008. One can only hope that Armenian and Azeri leaders will make tough choices and negotiate for a solution. Locally, both countries have a great chance to make the piece.

Background:

For those of you who don’t know, Nagorno-Karabakh is an indigenous Armenian region (called Artsakh by locals) within the country of Azerbaijan. This small territory declared its independence from Soviet Azerbaijan in 1991, less than seventy years after USSR chief Joseph Stalin gave Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijan. The conflict escalated into a war between Armenia/Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijan, killing thousands of people and leaving many more homeless.

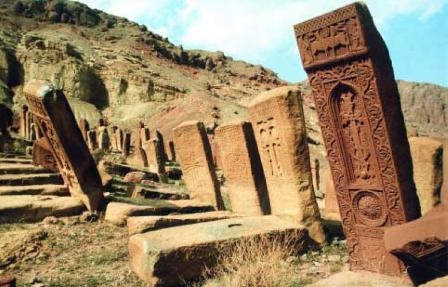

Today, Nagorno-Karabakh is an internationally unrecognized republic with a common border with mother Armenia. Nationalist sentiment is at peak high in Azerbaijan where most people see Armenians as invaders and aggressors. The sentiment was reflected in December 2005, when a contingent of Azerbaijan’s army reduced the largest medieval Armenian cemetery – Djulfa – to dust. (Official Azerbaijan until this day denies the destruction, even though it was videotaped.) While most Armenians are nowadays much less antagonistic against Azerbaijan, during the war, in 1992, armed Armenian groups massacred a few hundred Azeri civilians when fighting in Khojalu, although both official Armenia and some Azeri sources question some of the facts of the tragedy: particularly suggesting that Azeri forces deliberately banned Khojalu’s residents to leave through a humanitarian corridor the Armenian army had left for civilians. Furthermore, Armenians claim that the conflict itself started in Azerbaijan when mobs attacked hundreds of Armenian citizens, killing several dozen, in their homes in Sumgayit in 1988 while the Police stood by. Azeris claim that there were riots against their kin in southern Armenia at the same time.

Armenian and Azeri Attitudes:

In short, both Armenia and Azerbaijan see themselves as the victim and the enemy as the aggressor in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. And while abuses by both sides have been almost always symmetrical in the conflict, official Azerbaijan – until recently – has been using both verbal threats and disproportional acts of destruction. Threats have included official statements by Azerbaijan’s president to win Nagorno-Karabakh back by any price, including by war, and predictions by a senior Azeri military chief that Armenia will not exist in several years. Disproportional acts of destruction by Azerbaijan have included total elimination of all ancient indigenous Armenian monuments on its territory, especially in the exclave of Nakhichevan (another region granted to Azerbaijan by Stalin). This is not only inconsistent with Azerbaijan’s self-promotion as “the world’s most tolerant country,” but is also an act of cultural genocide (what I call “genocidal vandalism” in my honors thesis) which in no way contributes to the peace process.

Armenia’s diplomacy in the conflict has been more moderate, which may be a reflection of the following: Armenia’s victory in the early 1990s war, oil-rich Azerbaijan’s military boom, and limited open international support for Armenia in the conflict. Moderate diplomacy, nonetheless, hasn’t resulted in worldwide condemnation against Azerbaijan for blockading Armenia (although until George W. Bush, the United States didn’t give military aid to Azerbaijan). And in general, the world has been very careful not to take sides in the conflict (neither in the case of the Khojalu massacre by Armenians nor in the recent case of Djulfa’s destruction by Azeris): an approach which is difficult to determine as productive or not.

Ideal Solutions and Militant Positions:

One reason why it has been difficult to defend one position or another has been the polarized Armenian and Azerbaijani demands, a “normal” situation in every conflict.

Azerbaijan wants to return its borders to pre-1991, entirely reversing what the bloody war did before the 1994 cease fire. It says that Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh will be Azerbaijan’s citizens, but that they will never have the right or the option to succeed from Azerbaijan. In short, the legal concept of “territorial integrity” has been the supreme law and the sacred doctrine in Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan has about a million refugees who live in horrible conditions. Azerbaijan hopes that all these people will return to their homes, now under Armenian control. Armenians say and an Amnesty International report agreed last year, that Azerbaijan is deliberately ignoring its refugees and making their lives even miserable in order to gain international support.

Armenia says that Nagorno-Karabakh’s return to Azeri control would mean giving 150,000 Armenian lives into captivity. If Azerbaijan reduces unarmed ancient Armenian graves to dust, what will it do with live Armenians? Many, if not most, Armenians insist on also keeping the seven regions around Nagorno-Karabakh that Armenian forces gained control of during the war. While not many Armenians lived on these lands during the war, there are hundreds of ancient monuments that Armenians see as proof for their historic claim to the land. Some Azeris criticize Armenians for capitalizing on history and, thus, denying Azeri inhabitants the right to return to their homes. Some Armenians respond that Azerbaijan is trying to capitalize on rewriting history, and denying indigenous Armenians their right to self-determination.

On surface, Azerbaijan doesn’t agree to any solution that will let Nagorno-Karabakh be separate from it. In the same way, many Armenians consider the possibility of giving much of the seven surrounding territories back to Azerbaijan a loss. Neither party considers all the damage that has happened – and will continue to happen – to people in both countries because of the unresolved conflict. Nationalism has overridden cost-benefit analysis (with a human rights perspective) or mutual respect for the rights of the other.

Undemocratic regimes in both Armenia and Azerbaijan have perhaps contributed to the conflict. Wars unite populations, and perhaps the conflict has worked well for both Azeri and Armenian political elites. A few months ago, a former Azerbaijani serviceman (now studying in the United States) told me that Azerbaijan’s economic elite is using nationalism to hold power in the country. While Azerbaijan’s economy is booming due to oil exports, ordinary people are not experiencing change in their lives. Hatred against Armenia, some Azeris say, is the perfect tool for Azerbaijan’s rich class to distract the majority’s attention. And in Armenia, between 1992 and 1994, people would die from hunger and economic desperation. While the government was blaming everything on the war, several government-protected families were illegally becoming superrich. According to widespread claims, independent Armenia’s regime (both Levon-Ter Petrosyan’s and Kocharyan’s) elites stole billions of dollars from the people of Armenia through neoliberal privatizations of several industries and by other means.

Time for Change?

But even undemocratic regimes can solve problems, especially when their hegemony and reputation is at stake. In the last few months, there have been interesting developments in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. First, Azerbaijan’s ally and Armenia’s historic enemy Turkey demonstrated diplomatic will to cooperate with Armenia. Turkey’s president Abdullah Gul accepted his Armenian counterpart Serzh Sargsyan’s invitation to watch a soccer match between both countries in September 2008. The historic event, deemed as “football diplomacy,” was followed by recent meetings brokered by Moscow between Armenia and Azerbaijan where, for the first time, leaders of both countries seemed to be pleased. More surprisingly, Turkey has been reducing its pro-Azerbaijan rhetoric while trying to become a mediator between its two South Caucasus neighbors.

Many Armenians, who are usually skeptical in international relations given their experience of genocide, are discouraged with the recent development. Skeptics see Armenian president Serzh Sargsyan, who came to power following a bloodshed during the March 2008 post-election protests, as trading his own presidency for a solution unbeneficial for Armenia. Turkey’s involvement in the process is less encouraging for the residents of Armenia, a country that Turkey has been blockading since the Karabakh conflict.

While Turkey may not be a friend of Armenia, it sure has its interest in helping the Nagorno-Karabakh process. Turkey is under enormous pressure to open the border with Armenia (which Turkey thinks will help persuade US president-elect Barack Obama to back off from his pledge to recognize the Armenian Genocide). It will be very hard to open the border, though, without solving the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Thus, by helping to broker a deal between Armenia and Azerbaijan, Turkey’s current regime would silence the United States (and also its own ultranationalist deep state), have better prospects for joining the European Union, and make a claim to sort things out in the region (Turkey has surely expressed interest in brokering a deal between the United States and Iran, and unsuccessfully tried the same with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict).

Azerbaijan may be more interested in solving the problem now than in the past. Authoritarian leader Ilham Aliyev, the son of Azerbaijan’s former, now deceased, president Heydar Aliyev, just won a second (and final term) with the opposition boycotting the election (and giving him a perfect argument for a democratic victory). Not having to worry about reelection, Aliyev may be more interested in toning down his militant rhetoric. More importantly, the recent Georgian-Russian escalation over South Ossetia has likely demonstrated to Azerbaijan that war is not as good of a choice as Azerbaijan thought it might be. After all, Georgia not only didn’t win South Ossetia back, its attempt to get international sympathy faded away, if not being replaced with anger and distrust toward Tbilisi. Furthermore, the United States may want to partner with Azerbaijan even further more, especially in the case of an escalation with Iran, if it solves its problem with Armenia.

Armenia may be more inclined to change not only due to alleged pressure against president Sargsyan, but also due to the fact that an open border with Turkey will be a great asset for Armenia (Turkey thinks it may not be able to afford the border without a Karabakh solution). Furthermore, in two years, there won’t be many 18-year-olds in Armenia to qualify as soldiers. That’s because 1992-1994 are Armenia’s “dark and cold days,” when few families had children. So if there is to be war in the next four years, Armenia will have few bodies to fight.

A fight between Armenia and Azerbaijan, nonetheless, is not desired (at least at this time) by any of the superpowers, especially by the United States. Back in July, when I met with the acting US Ambassador to Armenia, I heard extremely nice remarks about president Serzh Sargysan’s offer of watching football match with his Turkish counterpart. The United States is seeking stability, especially with the mess that the Iraq war has created. Russia is also interested in stability between Armenia (a strong ally) and Azerbaijan (an ally), especially since Moscow’s interest in the Baku oil. Thus, internationally speaking, prospects for a peaceful Karabakh deal are possible, if not real.

Realist solutions:

Both sides need to accept that no solution is going to be perfect for either side. I don’t want to suggest what the solution should or will be, but it is clear what the solution cannot be. Azerbaijan cannot recover all the territories that it had before 1991; Armenia cannot retain all the territories that it gained after 1991. This is not a simple cliché, but a psychology that Azerbaijani and Armenian governments must start embedding in their populations. Any solution, though, would be a hard-sell both in Armenia and Azerbaijan. The governments in both countries might want to employ the same tactic they have used for a long time – information wars. Instead of dehumanizing the enemy this time, Armenian and Azeri TV channels (both are government-controlled to a large degree) should broadcast stories that rehumanize their neighbors. This strategy hardly needs to be called ‘affirmative propaganda,’ because there are so many true stories of mutual help and respect that can help in bringing change. One thing that is clear is that a peaceful solution at this time would be great for Armenia, Azerbaijan, their neighbors and the world.